Edward Dowse was born in Charlestown in 1756 into a family engaged in the carrying trade between the American colonies and Great Britain. At the end of the Revolutionary War, Captain Edward Dowse helped establish trade routes to China and the East Indies for a U.S. mercantile community banned from commerce with the British Caribbean, as well as the England. Dowse moved to an estate in Dedham in March 1798 to escape Boston’s yellow fever epidemic whereupon he retired from his maritime career. There his public spirited endeavors drew the attention of fellow townsfolk. This culminated in his election as a Democratic-Republican to the Sixteenth Congress in which he served from March 4, 1819, until May 26, 1820, when he resigned. Shortly afterwards, Dowse won office as Dedham’s representative to the Great and General Court. Dowse passed away in Dedham on September 3, 1828.

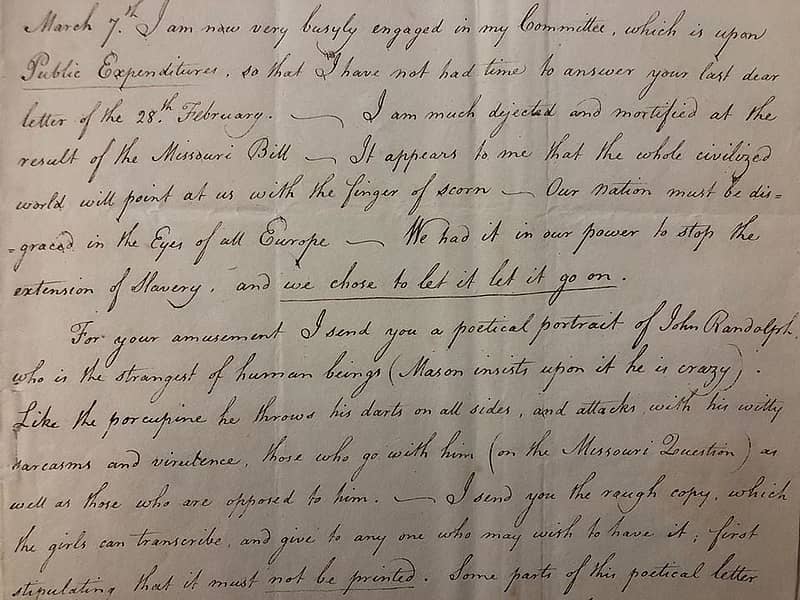

During his time in Congress, Dowse kept up a lively and loving correspondence with his wife Sarah. In the letters Dowse shared his experiences as a novice congressman and his correspondence frequently alluded to the bitter debates between northern and southern congressmen over Missouri’s proposed admittance to the union. This debate was occasioned by an amendment that Representative Tallmadge of New York had proposed. This amendment stipulated that Missouri could only enter the union after it had restricted further importation of slaves into the state. Moreover, all slave children born within Missouri were to be declared free at the age of twenty-five years. Southern congressmen argued that Congress lacked the power to either restrict slave owners from entering the state with their “property” or to force them to relinquish slaves when they reached the requisite age. As the debate about the Tallmadge amendment progressed, Dowse, an avid restrictionist, despaired because northern congressmen seemed to lack the eloquence of southern “anti-restrictionists” like the Virginia’s sharp-tongued John Randolph or Kentucky’s so-called “modern Demosthenes,” Henry Clay, that is, until Joseph Hemphill took the floor on February 6th, 1820. As Dowse related to his wife, the anti-slavery cause was well bolstered when “Mr. Hemphill from Pennsylvania came forward today and his speech has left the same effect as the charms of poetry upon my delighted imagination. It was like the Music of the Spheres. No, no, they (Southern congressmen) have not all the talent on their side. If sound policy, if reason, if wisdom, if virtue, if religion can ever successfully combat against love of money (the sole root of all evil), then shall we come off victorious in this great Missouri Question. Oh, Hemphill, delightful man, I thought of him till I fell asleep!”

Mr. Chairman, the present amendment does not interfere with the slaves now held by the inhabitants of Missouri, but by its operation their offspring will be free, the cause in which we are embarked is just as its object is designed to afford to the descendants of an unhappy race those enjoyments that heaven intends to give them; but we are met on the threshold of the discussion and told that Congress has no right to legislate on the subject. It is said that the power is too large, it has been compared to an ocean, and Congress ought not to be entrusted with it, the danger of its being abused is so great; It is contended that if Congress possesses this power, they might descend to the minutest act of legislation and introduce new states into the Union as mere dwarves, stripped of all grandeur and sovereignty.[However,] Congress possesses a string of powers, all of which might be abused, among others it possesses the power to levy and collect taxes, to borrow money on Credit of the United States, and declare war. These powers, if wickedly exercised, might not only jeopardize but might put an end to the existence of the Government. To make a comparison to the privilege of merely changing the relations of a territory into a state with the powers just mentioned would be truly like comparing a star to the sun.As to another remark that an act of Congress will be irrevocable and without responsibility, this position is incorrect. The inhabitants of Missouri are under no obligation to accept the terms [i.e. the Tallmadge amendment] proposed by Congress. They may appeal to the people who, if displeased with their representatives, can change them. And even if the terms are acceptable, they can be altered by the consent of both parties.

But it has been said that even this condition in restraint of slavery would manacle a limb of the sovereignty of the proposed state of Missouri , and bring her into the Union as an object of scorn, altogether unworthy of the association of her sister states. This picture is most unnaturally drawn; it ought rather to have represented her [Missouri] as the goddess of liberty. Our ancestors treated this subject in the true light in which liberty and slavery ought always to be considered. Is the spirit [of the Declaration of Independence] that warmed our breasts to pass for nothing? Is the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 [which banned slavery in the new states of the upper Midwest] to be reproached as a mere nothing?

I not will call attention to the peculiar kind of sovereignty that is to be withheld from the proposed state of Missouri. It is pretended that she will be deprived of the right of holding man in bondage. But how can this [holding people in bondage] be deemed a right? It is nothing more than a tyrannical abuse of sovereignty! All the laws on earth cannot make a right of it. When people are overcome and enslaved for want of ability to resist, these people do not lose their rights. The laws of the oppressing country may take from them their remedy, but slaves are only held by force because there is no ready remedy in their power to free themselves.

What can more directly attack the welfare of society than to hold a race of people in bondage? If the state of New York should enslave the small tribes of Indians within its limits, would the other parts of the nation acquiesce? Would it not rather be considered as offending against divine and human justice than as an exercise in sovereignty? It is a right that does not, and cannot, belong to the constituents [the people of New York] and of course cannot be deputed to the Supreme head [be claimed to be the will of God].

Gentlemen moreover have said that it would be cruel to oblige those who should be desirous to settle in Missouri to part with such slaves as had gained their affection, such as their favorite nurse or playmates of their childhood. [Actually, I suspect that] the number of such disruptions would be few. Nevertheless, this would be a happy opportunity for masters to give the best evidence of their attachment by manumitting (freeing) these favorites and taking them along as free persons. This would afford former slaves comforts for the remainder of their lives and this generous act would no doubt amply reward the master.

I have heard it said that slaves are as happy as the lower class of white people. If this is correct, it must be in consequence of the degradation to which they are reduced. Their faculties are not allowed the expansion which nature intended. They are kept in darkness and are unacquainted with their true situation. Slavery strikes the heart with abhorrence. This life can have no charms if it is not sweetened with liberty and if a slave has an accurate knowledge of his own condition, nothing can appear before him but sadness from the dawn of morning to the close of evening.

Finally, it is said that the restriction will interfere with private property when [the amendment] only says that children of slaves hereafter born shall be free. The evil [of slavery] is unfortunately permitted to remain in part of the Union, but beyond the limits of the old states, the power of Congress is competent to arrest its further progress. The rights of this unfortunate people only sleep: they never die and though ages and ages may pass away, the natural rights of posterity remain as perfect as that of their ancestors when first enslaved. Can you have deeds in your trunk to secure the bondage of the unborn? No! The natural rights of man forbid it! A law was passed in Pennsylvania in 1780 by which all children born after the passage of the Act were to be free at age 28. The constitutionality of this law was never questioned. And if they could be set free at 28, for the same reason they are now declared to be free at the moment of their birth! Pennsylvania’s citizens have remained faithful and ardent advocates of the gradual emancipation of the African race from that day to this!

Jefferson: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-40-02-0168

16th Congress: http://yamm.finance/wiki/16th_United_States_Congress.html

Transcripts of Dowse’s letters

Tallmadge Amendment and Speech

1820 Map of U.S.